Summary

Act 1

Macbeth, longstanding Thane of Glamis, has proven himself in battle against the treasonous Macdonwald, who was leading a rebellion against Duncan, the King of Scotland. Surveying the gloomy scene of their victory, Macbeth and Banquo—Macbeth’s fellow-soldier and best friend—happen upon three witches in the Scottish moors. The witches hail Macbeth, not only as Thane of Glamis, but also as Thane of Cawdor, and as the future King of Scotland. Confused, Macbeth insists that they must be mistaken; “the Thane of Cawdor lives,” he tells them, “a prosperous gentleman, and to be king.” How could these other titles be his when both were already promised to another?

Unknown to Macbeth, the Thane of Cawdor has also turned to treason, and been stripped of his title. As a reward for Macbeth’s victory, King Duncan awards him stewardship over Cawdor in addition to Glamis; and with the previous heir to the throne dead, Duncan announces his new heir to be his oldest son, Malcolm. Little do they know, however, how that throne weighs on Macbeth’s mind.

With the crown of Cawdor finally placed on his head, and despite Banquo’s words of warning, Macbeth cannot ignore the witches’ prophecy; and his wife, pleased with Macbeth’s newfound power, is eager to accelerate the fulfillment of the witches’ prophecy. Consulting with dark spirits, she hardens her heart, and determines that for her husband to become King, Duncan must die. When Duncan asks to visit Macbeth’s castle to celebrate, it’s not long before a plot is conceived.

Act 2

After a night of revelry, Banquo confronts Macbeth, worried about the witches’ prophecy. Macbeth dismisses him, telling him they will discuss it later; he has bigger things to worry about right now. As he approaches Duncan’s bedchamber, he sees a spectral dagger, reflecting the “bloody business” in his mind. Casting the vision aside, he enters upon the sleeping King, and murders him with his own hands.

That same night, Macduff, the Thane of Fife, arrives late. He goes to find King Duncan, and upon discovering the murder scene, raises the alarm to all in the house. With Duncan dead, Malcolm and his brother Donalbain fear for their lives and flee—Malcolm to England and Donalbain to Ireland—making them prime suspects for Duncan’s murder, and further removing suspicion from Macbeth.

Act 3

However, Macbeth is not without remorse. He regrets letting his wife talk him into killing Duncan, but more pressing on his mind is the witches’ prophecy. After they had spoken to him, they also spoke to Banquo, prophesying that while Macbeth would live to be king, it would be Banquo’s children who would ultimately claim the throne. Macbeth is furious, cursing the witches for giving him a “fruitless crown,” and a “barren scepter.” What good was it to be King if he could not pass the crown to his own posterity? In an attempt to protect his own regency, he orders assassins to kill his best friend Banquo, and Banquo’s only son, Fleance.

Certain of the assassins’ success, Macbeth and Lady Macbeth throw a party for the rulers of Scotland. When the assassins return, though, they report that while Banquo is dead, his son Fleance—the real threat to Macbeth’s throne—has escaped. As worry retakes Macbeth’s heart, he sees Banquo’s ghost in the feast hall, a grisly reminder of his terrible deeds—and stranger still, only Macbeth can see the ghost. Lady Macbeth struggles to save face, hoping to hide her husband’s growing madness from the others, but it is too late. Macbeth has already hatched another plan.

Act 4

His mind “full of scorpions,” he returns to seek advice from those who caused his discontent: the three witches. Answering his request, they show him grisly apparitions which tell him three things: 1) To fear Macduff, 2) That nobody born of woman can harm him, and 3) That he “shall never vanquished be, until Great Birnam wood to high Dunsinane hill Shall come against him.” Bolstered with courage, convinced that no man can harm him, he returns home. To his great joy, he learns that Macduff—the only man he need fear—has fled to England after Malcolm. Before Macduff can strike against him, Macbeth strikes first, ordering his assassins to invade Macduff’s home and slaughter his family.

In England, Macduff pleads with Malcolm to return to Scotland and rise up against the tyrant Macbeth. Malcolm resists, not feeling himself worthy to be king, but at Macduff’s insistence, he finally agrees to rally up 10,000 English soldiers to fight for Scotland’s freedom. Their sense of victory is short-lived, however, as news reaches them that Macduff’s entire family is dead at Macbeth’s hands. Filled with grief, Macduff swears to use his pain to fuel his hatred for Macbeth, and vows to fight him face-to-face.

Act 5

Back in Macbeth’s castle, a doctor consults with Lady Macbeth’s nursemaid, discussing the strange change that has come over her. As they speak, they see Lady Macbeth sleepwalking in a trance. She babbles fitfully, confessing to her part in the murder of Duncan, and lamenting that her hands will never be clean of his blood.

While this happens, Macbeth receives news that Malcolm’s soldiers—disguised with tree branches from Birnam Wood—are marching on the castle. Unfazed, and still convinced of his invincibility, Macbeth begins preparing for the assault, but it’s not long before he receives yet more jarring news: Lady Macbeth is dead. He takes a moment to pause, lamenting the brevity of life before hardening himself against the final battle.

After much fighting, Macbeth is finally approached by Macduff. Macbeth warns Macduff to flee, gloating that no man born of woman can harm him. At this claim, Macduff reveals that he was not delivered naturally by his mother, but by a surgeon’s knife—Macduff was not born of woman. Finally understanding the witches’ prophecy, Macbeth doggedly fights until the end.

Having taken the castle, Malcolm and his remaining men survey the scene of their triumph, lamenting those they have lost, and wondering if Macduff is among them. They are soon answered when Macduff returns to them, bearing Macbeth’s severed head and hailing Malcolm as King of Scotland. The throne restored to its rightful owner, Malcolm entreats his friends to help him rid Scotland of any remaining evil, and invites them to watch as he is crowned King.

Condensed Timeline

- Act 1

- Macbeth and Banquo meet three witches who predict Macbeth’s future as the king of Scotland, but that Banquo’s children will take over the throne.

- Messengers tell Macbeth that Duncan has made him Thane of Cawdor, and declared Malcolm heir to the throne.

- Hearing of the prophecy, Lady Macbeth makes a pact with dark spirits to harden her heart, and begins plotting with Macbeth to kill Duncan.

- Act 2

- Banquo confronts Macbeth, wanting to speak to him about the witches’ prophecy; Macbeth dismisses him and kills Duncan.

- That night, MacDuff also visits Macbeth’s home; he discovers Duncan’s body, alerting the entire household.

- Worried for his life, Prince Malcolm flees to England, causing others to place suspicion on him.

- Act 3

- Macbeth is crowned king of Scotland. He orders assassins to kill Banquo and his son Fleance.

- The assassins report Banquo is dead, but Fleance has escaped.

- Macbeth and Lady Macbeth hold a feast, where Banquo’s ghost manifests itself to Macbeth.

- Act 4

- Macbeth returns to the witches seeking counsel.

- Macbeth learns Macduff has also fled to England; he has Macduff's family killed.

- In England, Macduff convinces Malcolm to return with 10,000 English soldiers.

- When Macduff learns his family is dead, he swears to use his grief to fuel his hatred for Macbeth.

- Act 5

- While sleepwalking, Lady Macbeth confesses to killing Duncan.

- Receiving news of Lady Macbeth’s death, Macbeth laments the brevity of life while Malcolm’s soldiers begin their attack.

- Confronted by Macduff, Macbeth gloats of his invincibility; Macduff reveals that he has power to kill him.

- After the battle, Macduff hails Malcolm as King of Scotland, presenting him with Macbeth’s severed head.

William Shakespeare

Personal & Professional Life

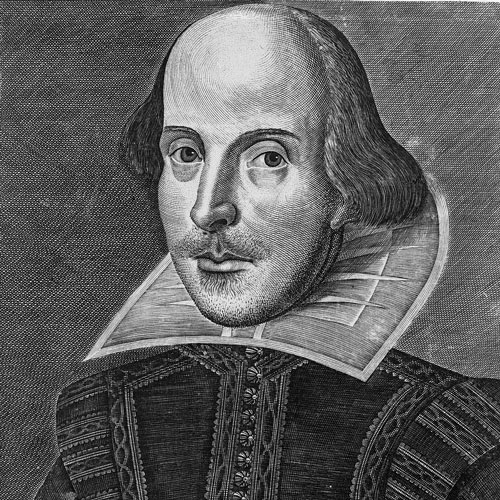

Born in England’s Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564, William Shakespeare grew to become possibly the most well-known playwright of all time, and a significant influencer of theatre, poetry, and the English language as a whole.

Very little is known of Shakespeare’s early life prior to his marriage to Anne Hathaway at the age of eighteen. In fact, very little is known of Shakespeare’s personal life as a whole, and even the details of his professional life are the subject of much debate, including the dates surrounding his career in theatre and as a writer. He was active in this field for somewhere between two and three decades before retiring in 1613, and passing away on April 23, 1616.

One well-known aspect of Shakespeare’s professional work, however, is his connection with playwright Christopher Marlowe. Though famous as rivals, it is widely suspected that Marlowe was a collaborator with Shakespeare on some of his works—most prominently parts One, Two, and Three of Henry VI—and it cannot be denied that Marlowe’s own works influenced Shakespeare’s later writing.

While many of the details of Shakespeare’s life can only be left to speculation, the impact of his works can be readily seen. No other playwright’s plays are produced more often, and words and phrases originally penned in these stories remain popular in today’s vocabulary. Even to those relatively unfamiliar with his works, Shakespeare is a household name. It cannot be denied that even four centuries after his death, Shakespeare remains one of the most famous and well-beloved men in history.

Writing Macbeth

In his book The Genius of Shakespeare, Jonathan Bate explores a popular traditional tale about Shakespeare’s inspiration in writing Macbeth:

“In the summer of 1605, King James, still new to the English throne, visited the University of Oxford. At the gates of St. John’s College, three undergraduates cross-dressed in the female garb of sybils emerged from an arbour of ivy. The first hailed him as King of Scotland, the second as King of England, and the third as King of Ireland. The first also reminded the King that three prophesying sisters had told the ancient Scottish Thane Banquo that, though he would not be king himself, his descendants would one day rule an immortal empire. (S)he explained that since King James claimed descent from Banquo, the sisters were now reconfirming their prophecy.”

The students referred to stories found in Holinshed’s Chronicles, a series of books containing historical stories of England, Scotland, and Ireland. One such story involved a Scottish ruler named Banquo meeting witches and receiving a prophecy, exactly as told in Macbeth. It is widely believed that Shakespeare used this account as inspiration for the story of Macbeth, though certainly with some artistic liberty taken.

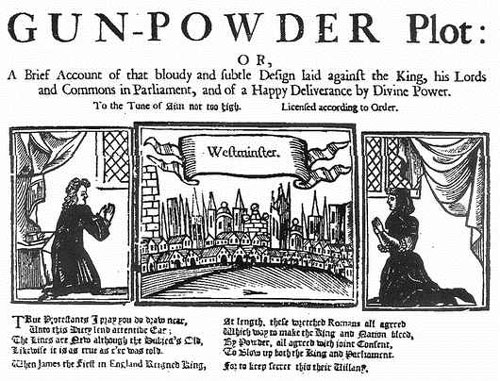

Another theory attaches Macbeth with the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in which an attempt was made to kill King James by blowing up the House of Lords. With the play’s plot of an attempt against a king’s life, it is supposed that Shakespeare was using the play as an attempt to warn King James against such attempts in the future. However, Bate seeks to keep such theories in check:

“But to make the play

‘topical’

in this way is purely suppositious. To read it thus depends on phrases such as ‘tradition has it’

, ‘to suppose Shakespeare was told’

, and ‘may well have been played’

. Besides, Macbeth is not fundamentally about King James’s descent from Banquo, persuasive as it is to see connections with his interest in witchcraft and to hear allusions in the Porter’s monologue to the ‘equivocation’

of the Jesuit Father Garnet in his trial following the Gunpowder Plot against the King’s life.”

This passage does bring up a more widely-affirmed point, namely King James’s interest in witchcraft. So strong was his interest, in 1597 he published his Daemonologie, a book dealing entirely with witches, magic, and necromancy. It is highly likely that, knowing this, Shakespeare included Macbeth's iconic depictions of witchcraft as a specific nod to the King’s interests. In fact, another less scholarly tradition holds that in writing the play, Shakespeare consulted with real witches so he could provide an authentic ritual to be portrayed in the opening scene. So displeased were the witches with such a wide revealing of their rituals, the tradition holds, that they cursed the play, leading to the still-strong superstitions among theatre-goers that Macbeth is an unlucky play.

Analytical Quotes

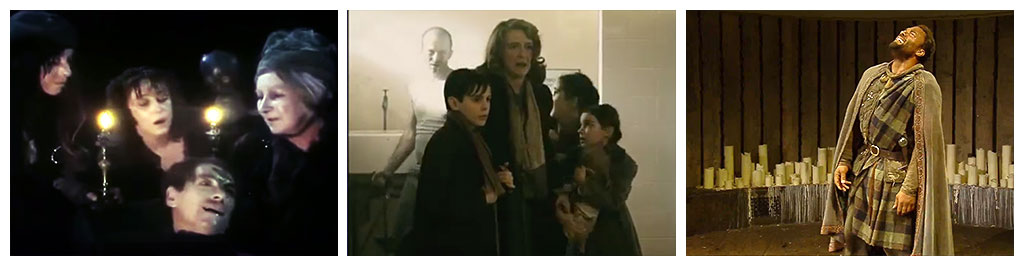

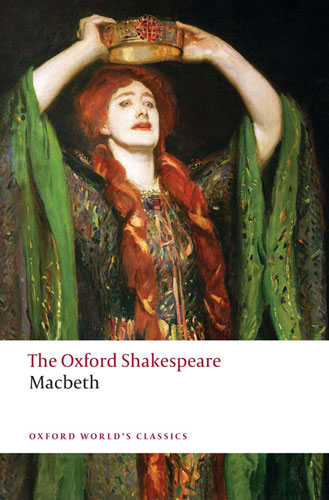

In his introduction to the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Macbeth (2008), Nicholas Brooke examines the use of illusion throughout the play; a practice common to all theatrical works, but somewhat exaggerated in Macbeth. The illusions not only add to the theatrical experience, but they act as something of an outward symbol of the characters’ inner workings.

“All theatre depends, in one way or another, on illusion, but Macbeth is exceptional in affirming continuously a direct contradiction of the natural conditions: the transformation of daylight into darkness is a tour de force which establishes illusion as, not merely a utility, but a central preoccupation of the play, dramatically announced by an opening unique in Shakespeare’s plays, the use of the non-naturalistic prologue by the Weïrd Sisters in [act 1, scene 1]”

(pp. 1).

He goes on to explore nine particular examples of illusions from the story:

“Darkness in daylight is established symbolically by torches and candles whose effect depended on the power of theatrical convention to which a modern audience cannot respond so directly as a Jacobean one, but that is greatly extended linguistically by direct statements, allusions, or indirect suggestion of verbal imagery.”

Though Macbeth was written to be viewed on a stage, the reader can still feel the effect of the darkness because it is expressed so clearly through the text.“The Weïrd Sisters are visible to us, and to Macbeth, and to the less questionable sight of Banquo (a touchstone of common sense, like Horatio in Hamlet, even if less solid). The Sisters cannot be reduced to projections of Macbeth’s mind, they are not mere delusions; though just what Macbeth and Banquo see is very questionable.”

The visual effectiveness of the Sisters depends more on what they are not than what they are, as Banquo describes:What are these…That look not like th’ inhabitants o’th’ earth / And yet are on’t?”

The ambiguity works to great effect, letting the reader’s mind conjure a more vivid image than a more specific description could.“The dagger is an opposite case: The Weïrd Sisters are attested by sight (ours and Banquo’s, besides Macbeth’s) but are indefinite in form; the dagger is entirely specific in form though not literally seen by anyone—even Macbeth knows it is not there.”

Here, the specificity of dagger’s description is equally as effective as the vagueness of the Sisters’. It also shows us the beginning of something twisting in Macbeth’s mind—a foreshadowing of darker transformations.“Banquo’s ghost is different again: it is seen by Macbeth, it was seen by Simon Forman at the Globe in 1610-11, and it has been seen by audiences in most productions since. Thus far it contrasts with the dagger, but is also in a different case from the Weïrd Sisters because it is seen by no one else on stage.”

This is another sign of Macbeth’s progressive twisting of the mind, but a more express one than the dagger; both because the audience can see it, and because it is a more direct emblem of the wicked deeds Macbeth has already committed.“The apparitions in [Act 4, Scene 1] are a climax to this sequence of stage illusion tricks, though the formal liberation is not technically the most surprising or exciting (it neither requires nor gets the conjuring-trick surprise of the others). It can use elaborate machinery, but it can equally be done with simple effects—cauldron, smoke, a trap, or even less.”

These illusions build upon the already-established illusion of the Weïrd Sisters, heightening their unknowable nature, while at the same time doing their own work to tighten the twisting in Macbeth’s mind.“Lady Macbeth’s sleep-walking in [Act 5, Scene 1] is essentially about delusion, but caused by psychological disturbance not by supernatural agency; our recognition of a natural phenomenon is endorsed by Doctor and Nurse, who also recognize a connection with guilt dreams in its jumble of displaced memories.”

While Macbeth’s madness is manifest in other illusions, Lady Macbeth’s is manifest in her own person. The frenzy in her mind becomes so powerful that her body loses control to it, acting independently of her own will.“Birnam Wood, whose moving is an exercise in camouflage of a kind still a commonplace of infantry tactics. Illusion is being reduced to rational explanation, …the audience is given a full explanation of Birnam Wood before the event.”

Finally, an illusion whose nature we can understand; one created by men, in stark contrast to the supernatural illusions heretofore discussed.- Macbeth’s Head:

“Macbeth does not begin with an illusion of realism, but it does end with one:

As Malcolm expounds, the butchered head of the “Butcher” himself.‘Enter Macduff, with Macbeth’s head’

—presumably stuck on the end of a pike.” - Verbal Illusions:

“The eight distinct forms of dramatic illusion discussed so far are all dependent on staging…The ninth, recurrent throughout the play, is the purely verbal creation of a highly visual but unseen world of babes and cherubim, rooky wood, murdering ministers, and horses eating each other; the unusual stress on sensory actuality leaves audiences with an undefined sense of having seem, smelt, touched far more than we have, though, as with Macbeth’s dagger, we know there’s no such thing.”

Facts

- Originally published in 1623 in the First Folio (believed to have been first performed in 1606).

- Nearly 2,000 publications since then, according to Goodreads.

- Translated into dozens of languages.

- Over two dozen film adaptations, including films set in feudal Japan, a café in Pennsylvania, a gang war in Chicago, the Mumbai underworld, and more.

- Macbeth has been portrayed by actors who have played Gandalf (Ian Mckellen), Jean-luc Picard (Patrick Stewart), Gilderoy Lockhart (Kenneth Branagh), Steve Jobs (Michael Fassbender), and more.

Discussion Questions

- Who was more at fault: Macbeth, or Lady Macbeth?

- When was the point of no return for Macbeth?

- What caused Lady Macbeth to reconsider her actions?

- What is Macbeth trying to communicate in his “tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow” speech?

- What was the significance of the dagger Macbeth saw?

- Why could only Macbeth could see Banquo’s ghost?

- Could Macbeth have subverted the witches’ prophecy?

- Could Macbeth have stopped Macduff?

- Could Macbeth have redeemed himself?

- Could Lady Macbeth have redeemed herself?

Out, brief candle. Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player, that struts and frets his hour upon the stage, and then is heard no more. –Macbeth

Additional Resources

- Oxford World's Classics edition of Macbeth

- Oxford School Shakespeare edition of Macbeth

- Pelican Shakespeare edition of Macbeth

- The Genius of Shakespeare by Jonathan Bate

- Shakespeare and Modern Popular Culture by Douglas Lanier

Web

- CliffsNotes Study Guide

- Sparknotes Study Guide

- No Fear Shakespeare Modern Translation

Film

- Royal Shakespeare Company Production (1979)

- Great Performances Production (2010)

- National Theatre Live Production (2013)

- Justin Kurzel Production (2015)